Listening to the Middle Ages with Jonathan Berger

Visit

Sound, Space, and Sensing the Unfathomable

at Stanford University

Episode 327

Since the new year, we’ve heard about both the development of medieval music and what it was like to live in the cultural hotbed of fifteenth-century Florence. And now, we’re going to bring it together in a way that has only been heard by a handful of people in almost six hundred years. This week, Danièle speaks with Jonathan Berger about capturing the sounds of the past, what they can tell us, and the remarkable sound of one specific moment time.

Transcript

Danièle Cybulskie: Hi everyone and welcome to Episode 327 of The Medieval Podcast. I'm your host, Danièle Cybulskie.

Since the new year, we've heard about both the development of medieval music and what it was like to live in the cultural hotbed of fifteenth-century Florence. And in today's episode, we're going to bring it together in a way that has only been heard by a handful of people in almost six hundred years. Because today we're jumping in a virtual auditory time machine and listening to the Middle Ages.

This week, I spoke with Dr. Jonathan Berger about capturing the sounds of the past. Jonathan is an award-winning composer, Denning Family Provostial Professor in music and the director of the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics at Stanford University. He was the founding co-director of the Stanford Institute for Creativity in the Arts, now called the Stanford Arts Institute, and the founding director of the Yale University Center for Studies in Music Technology. And he has dozens of publications to his name, in addition to his musical compositions. His new project is Sound, Space, and Sensing the Unfathomable, which aims to recreate the sounds people would have heard in the past. Our conversation on how this remarkable feat is achieved, what it can tell us about the people of the past, and what one specific moment in the fifteenth century might have sounded like is coming up right after this.

Well, welcome, Jonathan, to talk about sound and music and all the things that are built for a podcast medium but I haven't gotten to before. It's so nice to meet you. Welcome to the podcast.

Jonathan Berger: It’s a pleasure to be here, Danièle.

Danièle Cybulskie: Okay, so you are trying to recreate sounds that people might have heard hundreds of years ago. What got you started on this project to begin with?

Jonathan Berger: So, I'm neither a medievalist, nor a historian, nor a musicologist, nor a scientist. I'm a composer. And during a year I spent in Rome about six years ago, I was working on a piece where I wanted to recreate the acoustic environment of a particular area. And so, in order to learn how to do that, I started learning to record sound in highly reverberant spaces. Churches, catacombs, caves. And as I learned more about the technology, I got more interested in the question of how and why did people build these hugely reverberant spaces? They go back many, many centuries, but it's actually… the Middle Ages was sort of the height of building these massive cathedrals where sound gets completely distorted and completely munged. And so, I was interested in both the creation and reception. What happens when someone creates a sound in these spaces? And even more so, what happens when someone creates a sound for these spaces. What are they thinking? And do they manipulate the acoustics of spaces or do they manipulate their music to fit the spaces? So, I became sort of obsessed with this, and I spent most of the year in Rome going from church to church and creating these acoustic models. In the subsequent years, mostly my very bright graduate students helped me build these models and build these spaces where we can actually recreate the sound of any space that we've modeled with great accuracy in a very small space, which allowed us to build all sorts of experiments about how people interact with these spaces and how people create music in these spaces. This is an ongoing project.

Danièle Cybulskie: We're going to get into how this happens because it's absolutely fascinating. But I think the question that I need to ask is, what do we learn from listening back this far in time? What are we looking for? What's the value of hearing these things that are so old?

Jonathan Berger: I'll get to your question directly in one second, but let me preface it with one of the unexpected consequences – or the emergent pieces – of my research is that I was contacted by numerous archaeologists and paleontologists who came with the – you know, once they heard what we were doing – their argument was, we deal with material, but we have no way of dealing with the actual sound, the sort of the ephemeral aspects of life in these spaces that we're studying. So that truly excited me, and I think that that really sums up my excitement about this, that it gives us a sense of understanding why and how these massive structures were built in order to intentionally distort sound.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yes, this is the question, because we're going to be playing a clip right at the end of our interview that demonstrates some of the research that you've done. And you do get muddied sound in there, which does beg the question, why would you do this? Are you just building this for the visuals when auditory… the auditory nature of the mass, for example, is such an important part of it. So, yeah, it's an important question that you're asking.

Jonathan Berger: Well, the auditory nature is important, but it's not clear. I mean, there's been a constant struggle throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance and beyond between the balance of clarity and obscurity of sound. Right. So, clarity and intelligibility is necessary in order to transmit the word of God in a sacred space. But the obfuscation of sound, right – the distortion of sound – is important to give the sense of richness and transcendence and awe. And those two polarities in perception become really central to how sound was manipulated in this period.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yeah. And as you're saying, when people are living within these spaces – not living within the church, but living with access to these spaces all the time – composers like you are thinking about the acoustics when they're creating their pieces. And so, this might give us an idea as to how they're planning things in order to balance something like awe, right? Okay, so let's get into the technical aspect, because this is fascinating. So, you need to, at first, figure out what a room sounds like in a way that is consistent. So, you can't just have somebody shouting hello in the middle of a space. How do you figure out, in a way that's consistent, what a space sounds like? I think this is amazing.

Jonathan Berger: Again, not to drag this out beyond what you want, but let me start before that. How do we choose those spaces? Right, so we need to find spaces that were ideally not changed radically since they were built. That's actually very rare. Particularly sacred spaces. Sacred spaces… in Catholicism, for example, every pope would come in and completely alter their church. They'll bring in sculptures of themselves. They'll bring in, you know, they'll change things around. They'll build chapels. So, it's very rare that we find a space that we can say, we know this hasn't changed architecturally. And the second thing is that we want to find places where we know what sounds were made in those spaces. So, finding the materials is sort of the first part. Okay, so now to your question. First of all, again, let me preface this. I'm sorry, this is my habit is I go into tangents very quickly, so stop –

Danièle Cybulskie: No, I love it. I love it. Go ahead.

Jonathan Berger: The first thing to keep in mind is that… let's think for a moment of a room or a building as a musical instrument in itself. Any sound that's made in that room is distorted and changed and filtered by the properties of that space. Right. So, I'm making the sound now. I'm in what's called a near anechoic space. There's very little reverberation, right? But even here, my voice is bouncing against the walls and coming back. And, you know, it's an incredibly complex network of activation that happens when a sound is made. And so, our purpose is to try to capture the nature of that activation. So, we go into a space we either know, or we need to assume, from where sound was made. That's where we set our target of where the sound is created. And then we record from a large number of spaces, but particularly spaces where we think the sound was heard. That's a problem in itself in architecture.

So, ideally, to simplify it, we have one space, one place, say, on the altar, where we know sound came from. And then we have one place in the middle pews, which was sort of the ideal listening location. We set a speaker on the altar, and we also put myself on the altar with a balloon, and we pop a balloon and record it in the space with a microphone that is tetrahedral, that records from many, many different angles and sides. So, then we capture the sound of the balloon pop, and that gives us a sense of how sound is transmitted and dissipated. We're able to measure exactly when the sound dies away. And then the next thing we do is we create a long sine wave sweep. So, we sweep a sound that starts from zero hertz going up to well beyond the range of audibility. And with that, we're able to study at each change of frequency, what the nature of the building… what the characteristics of the acoustics do at that point. So, we're able to capture the resonance as well as the decay. And with that, we have all the information that we need to build what's called an impulse response. Right. So, it's how the sound responds to the balloon pop or the impulse. And with that, we create a set of sound files of the impulse responses. And then by a process called convolution, we take any sound coming into that and we convolve it with the impulse, and then we were able to recreate how that sound would sound in this space.

Danièle Cybulskie: That's incredible, because, again, I would be wondering, how do I make a consistent sound that's always consistent? And having a balloon pop is genius. I don't know who came up with that, but that's a genius idea.

Jonathan Berger: Well, I mean, the ideal way to do this in historical architectural acoustics is to shoot a pistol, but they would never let me do that in Rome. In fact, they barely let me do it with balloons. But, yeah, it has its own issues. No two balloons are the same, the size are not the same. So, there's a lot of variability, but we do a lot of it, and then we average it out, we figure it out.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yeah, I imagine they won't want you shooting pistols in the middle of a church. It might ruin a fresco. And then some of the other places you've measured include Paleolithic caves. And they don't really want you to shoot a pistol in those either.

Jonathan Berger: Absolutely. Right.

Danièle Cybulskie: And I love that this can be extended. This type of research can be extended to Paleolithic sites to medieval sites, to later sites as well, to have an idea –

Jonathan Berger: Absolutely.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yeah. And one of the things I think that you're saying that's really important is we're talking about reverberation of sound. And also it really applies to the materials that something is made of, which is why it needs to be so consistent. So, for the… the medieval example that you've used is a church, can you tell us a little bit about what the interior of the church is like, what the sound is bouncing off of?

Jonathan Berger: Okay, so the church that I sent you an example of is the Duomo in Florence. So, it's at the edges of medieval-dom, where it's the year 1436 is when Brunelleschi completed the magnificent dome, which is sort of the centerpiece of Florence, was actually built to be the centerpiece of Florence. You know, the rulers and government wanted Florence to have this outstanding feature, so they built this monumental dome which defied architectural principles, but also set these incredibly bizarre acoustic conditions that have yet to be really reconciled with.

So, there's this massive space. And indeed, we did exactly what I described. We popped balloons from the altar. We also popped balloons from… from various chapels, and we recorded them across a wide number of spaces from the outside, from the entryway to the church, all the way up to close to the altar with the assumption that if the church was filled in the day of consecration, people are hearing this all over the place.

Right. So, now the next thing, and this is where musicologists are going to jump on my case here. One of the most famous composers in Europe at the time was Guillaume DuFay. Guillaume DuFay was brought to Florence and commissioned to write the consecration piece for the Duomo. And he writes this magnificent piece called Nuper Rosarum Flores. It's going on the idea that Florence is about flowers. And so, this is celebrating the role of the flower. And he writes this piece, and it has become one of the monumental pieces in music history. Anyone who takes a class in early music will have to learn this piece. And there's some great controversy about this piece, which fits into my story. I'll put that aside and keep it for if you want me to talk about it later. But what we don't know is where the piece was performed and exactly when the piece performed. We know that DuFay brought the piece to Florence on the day of consecration, which was 1436. We can assume that it was performed in the church. And most likely, because the dome was the feature that's being celebrated here, was done either under the dome or on the altar. And so, we wanted to reconstruct that sound, which has never really been done. Nobody has really stopped and said, well, what did that piece sound like in the place for which it was written?

Danièle Cybulskie: Yes, at the time.

Jonathan Berger: So that's what we’ve done. Yeah.

Danièle Cybulskie: So why did you choose the Duomo for this experiment? Because there's churches everywhere, as you said. Why this one?

Jonathan Berger: Well, the Duomo is a magnificent place and I love Florence. The wine is good, the food is great. But the more academic reason is that Florence boasts a number of magnificent churches, and we've measured quite a few of them. The two that became interesting in my research are the Duomo, which was sort of the central… this is the church in Florence, and San Lorenzo. San Lorenzo is just down the block. That's a church that was built for the Medici family, for Lorenzo de Medici. So, these are the two most important churches in the fifteenth century. They're very close to each other. And more importantly, Brunelleschi, the architect who did the dome for the Duomo, also was involved in the architecture, the architectural plan of San Lorenzo.

They're two radically different churches. The Duomo has this monumental dome with this hugely long acoustical trail, reverberant trail, and San Lorenzo has a flat roof which is much more amenable to clarity of sound. So here you have these two churches that are close to each other, built approximately the same time by the same architects, and have radically different acoustical features. And then, as time goes on, the composers who were selected to write for these places, some of them write for both places. And musicologists have no clue what piece was meant to be played in which space. So one of the mysteries that I'm working on now – and again, musicologists will jump all over me for even saying this – is that I think that we can take acoustics into account in figuring out what composer was thinking… you know, what place the composer was thinking of when he – typically “he” – wrote for this space or the other space.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yeah. So, one of the things that you mentioned in the research is that this might give an idea of the tempo of a piece. Can you tell us a little bit about what we have that tells us how a piece should be performed? What is left to us from the Middle Ages? Because I think not many people have seen any music from the Middle Ages.

Jonathan Berger: First of all, music in the Middle Ages was notated very sparsely. There are no indications of tempo, there are no indications of dynamics, how loud to play it. There's no indication of stopping and starting or slowing down. Or where to rest. There are no indications of even meter. There are no bar lines, right? So, the text drives the organization. And in fact, in much of the music that was written, there are no scores. There's no one document that puts all the voices together. A lot of the music that we've been studying is written in parts. So, the composers wrote them directly to each voice had its own part. And then you have to sort of put it together like a puzzle.

So, music notation is inherently vague. Even today, Western music notation leaves much to the choice of the performer. Even now, when we have the ability to give quantifiable metrics to how to play a piece, you know, we can give exact tempo. Typically, composers like myself will say, well, play it fast. Play it pretty fast. Play it sort of fast. And that really means nothing to historically recreate it. So, there's a whole field called Historically Informed Performance Practices. Right? This is a field that's been going on for the last fifty years, or sixty years, almost a century. And what they're doing, what they've done, is to recreate the instruments that play them and recreate the sounds and recreate the conditions. But they really have little thought about how fast to play these pieces. And if you listen to – this is getting off those academics who really take this seriously, but – if you listen to most recordings of sacred music or even secular music from the sixteenth century backwards, they're typically recorded in these highly reverberate churches. That gives this sense of, oh, how wonderful it sounds in this church. But there's no reality there. There's nothing that says, oh, it was really done in this church.

And then the issue of tempo, the issue of how fast to do it. If you think about two adjacent notes in a piece, if the decay time in the hall in the place that you're playing, this is ten seconds, then it'll take ten seconds for the sound of note A to die away while note B comes on. If that is not a factor in what you're thinking about how fast play this piece, then you're going to come away with music that's incredibly blurred. And that's often the case when we listen to early music.

Danièle Cybulskie: Well, it's interesting because the piece that we're talking about that I'm going to play later is one that involves lyrics. It doesn't involve any instruments. And I'll ask you a little bit about this in a second. But it's just voices, which means in this case, they're speaking words that you're meant to hear and understand. And so, the tempo is hugely important when there's reverberation involved, or else you're just not going to understand what's being said.

Jonathan Berger: Correct.

Danièle Cybulskie: So, this piece, can you tell us what is it comprised of? How many voices are we talking about? Is it composed for what type of people? Because there is also the question always of the gender of the performers, the age of the performers, that kind of thing. So, tell us what we know about this piece.

Jonathan Berger: Well, it's written for four voices, all male. Females didn't sing in churches. So, even the high voices, the soprano voices, were done by typically castrated young people whose voices were then trained to be the upper voices. So, this strange Western phenomenon of castrati singers was important in these frameworks. Right. So, it's four voices. Now, we don't know how many singers sang on each voice. Was it a choir of 200 voices where they were split evenly, or was it four solo voices? We don't know. So, we've played with both of these, and what we did is we took a wonderful early music group in Amsterdam, the name of the group is Stile Galante, and they recorded music – I've been working with them for many years – they've recorded this piece and other music that I've studied in a space like this, in a near anechoic space, so that we have their sound without any reverberation. And then we were able to convolve it, to produce it as if it's through this space. So that's how, when you play it, you'll play one version that's completely dry and then one version that you hear in the space.

Danièle Cybulskie: So, when I do play it, the reverberated version – the version that is supposed to be replicating what we would hear in the Duomo itself – is this meant to be an empty church, or is this meant to be a church full of bodies? Because, again, this changes it.

Jonathan Berger: That's a wonderful question.

Danièle Cybulskie: Especially because if it's packed for the consecration, it's going to sound different.

Jonathan Berger: Danièle, that's such a great question. And here's my uninformed, non-musicological answer to this. What we do know is that a walkway was built from Santa Maria Novella, where the pope was staying, to the Duomo, and that he and his entourage walked for the consecration to this space. We also know that much of the town came out to be a part of this, so it's likely that the place was packed, but we don't know that for sure. There's no great evidence of that. There are just descriptions. And again, we don't know how many voices were singing. So, we're taking a leap of faith here and saying it's a fairly small choir that's singing in this highly reverberant space. And the place is packed full. Now. We can't simulate it packed full. I mean, we can play with it, and we've tried to. So, you're hearing a version as if it's being done in a reasonably empty space. I'll tack onto this that when we were doing this, we had to do these studies in the middle of the night because Florence is a pretty loud town. And so, we waited for the place to die down. And then the only thing that you hear in the piazza outside the Duomo at midnight are street musicians that are playing. And so, I had to go out and bribe them not to play. And in fact, they said, well, this is the first time I got paid for not making music. But then we… you know, so we were able to get a reasonably quiet version of that space. But the place was never quiet.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yes, exactly. Even if everybody in Florence is in Duomo at the time, there's still going to be sound outside. It's just never going to be everybody. And one of the papers that I read in preparation for this interview talks about a mosque in which there's always going to be sound outside. And this is just part of the human experience.

Jonathan Berger: Absolutely.

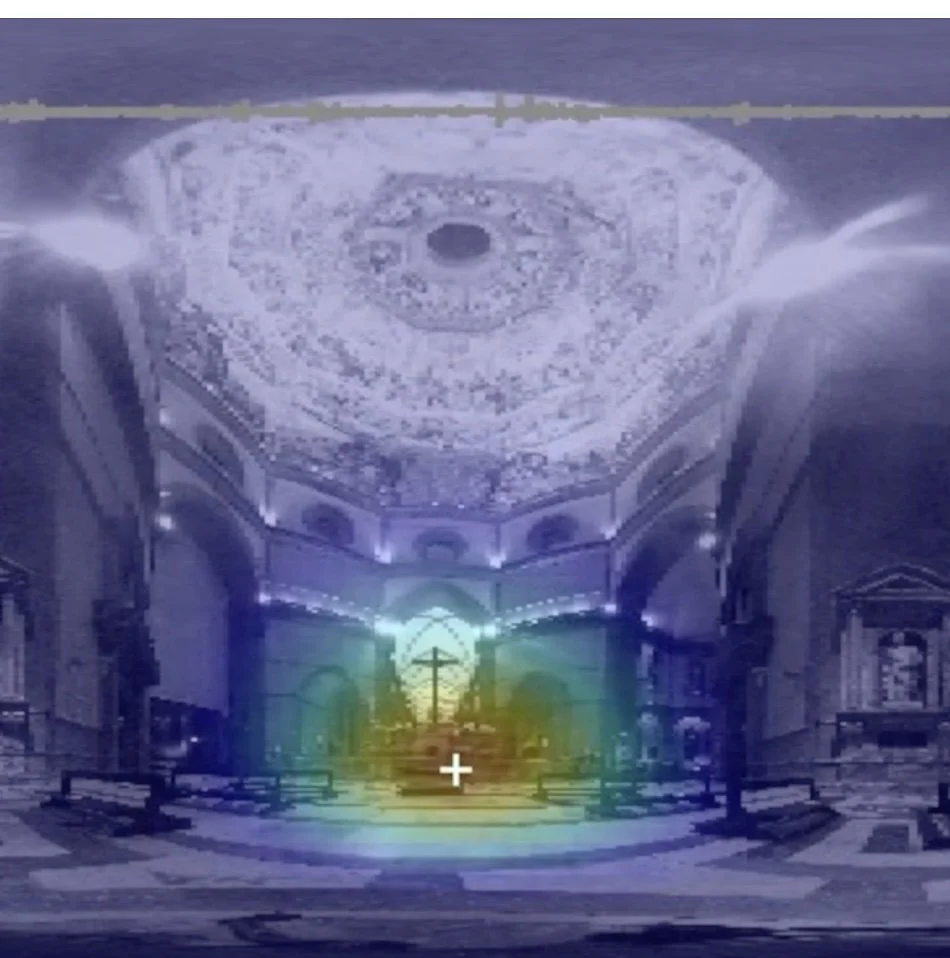

Danièle Cybulskie: So, you've created this simulation and, as you say, recorded it, the balloon pop in different spots within the church. And part of this research was to create VR for this. So why add the visual to something like this? Why not just be listening to the recording? One recording? Why make it a VR recording?

Jonathan Berger: Yeah, great question. There are two main reasons. The two main reasons are, one, we're trying to understand what are the acoustic attributes that create a sense of awe, that create a sense of transcendence. You know, if you can imagine going into a space like the Duomo or any... any cathedral, or even more so, a truly medieval place, you know, Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. These spaces are massive. And you walk into the space, and the visual sense alone makes one feel small and gives a sense of vastness. And that's one of the factors in creating this sense of awe.

The acoustic factor is the sense of the erasure of clarity. There's a sense of I don't know where I am. I mean, the sound is so... is coming from everywhere. I can't tell where I am. So, the sense of sensorial confusion is a factor. And we're trying to isolate both of those factors. So, we're doing these experiments with visual cues and without visual cues, where someone is brought into the virtual space and can actually maneuver through this space. But we're also doing it blindfolded to see if we can just... Can we elicit awe just from the sound itself? So that's one factor.

The other factor is exactly what I said before at the beginning, which is archaeologists and paleontologists and Egyptologists come to us and say, we want a representation of how things sounded. Many of these spaces, I mean, in archaeology, it's typical that an archeological site was dug up a hundred years ago, and then architectural plans were drawn, but then were covered up. So many of these spaces are inaccessible. The caves in Chauvet are not accessible to the public. The tomb in Egypt that we're studying is covered up completely. We just came back from Peru, where we're looking at an Inca site that's built below a church. And while the place is there, inaccessible, the site that we're trying to recreate is just the Inca site without the church. And so, we need to do a lot of manipulation to do this. And so virtual reality gives us the opportunity to engage in these otherwise inaccessible spaces. And that's important for research, and it's equally important for the public.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yes. I love this, because people might think that history, that musicology, that performing or composing is just dry, dusty stuff. It's just you and papers, but here's people crawling through spaces and sticking a boom in a cave to get a reading. I love this. So, there you go. Study history, study music, travel the world. And one of the things that you haven't mentioned yet, but there are implications that doing this sort of research is important for preservation. So, can you tell us a little bit about how those things go together?

Jonathan Berger: Sure. My work is inspired greatly by work of my colleague Jonathan Abel and medieval art historian [Bissera] Pentcheva, and they were working on Hagia Sophia. Right. Hagia Sophia was built in the 6th century by Constantine the Great. It became a Byzantine church, and a lot of the Byzantine rite and ritual was written for this church. But over time, the church changed architecturally, and, of course, it became a mosque, and then it became a museum, and now it's a mosque again. And with each – like the pope's – with each entry, acoustical features change. Right. And so, trying to recreate what it was like when it was built – built in the sixth century – and trying to understand what Byzantine chant in the ninth century might have sounded like in that space is a challenge. So, we have to take certain leaps of faith, but we try to reconstruct the conditions as best as possible.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yeah. I'm thinking about the type of preservation that happens when such precise measurements are made, because we all witnessed the fire at Notre Dame. And it turns out that the work of historians, medievalists, that measurement of the cathedral to the millimetre, really helped with preservation. And this is… some of the work that you're doing, contributes to that sort of thing as well, right?

Jonathan Berger: Yep, yep, yep. My former PhD student Elliot Canfield-Dafilou was on the team that reconstructed the sound in Notre Dame, and they had fantastic questions that they had to ask. The… Recreating the exact type of wood that was used, which they did. So, in order to recreate these conditions. Yeah. You really have to relive the moment.

Danièle Cybulskie: Well, I have to ask this question because when we first set up this interview, it was going to be shortly after Christmas. And I was thinking, these are the type of questions people are asking you around the holiday dinner table, like, what is this for? And it's useful for all sorts of things, including preservation of precious buildings.

Jonathan Berger: Yeah. And even answering really fundamental questions. So, the Egyptologists that we're working with, they're trying to understand a funerary site in ancient Saqqara. So now, we're third dynasty. We're well before Europe, period. But they know everything about the tomb, and we're able to reconstruct that. And we have this VR reconstruction of it and the acoustic reconstruction. What they don't know is anything about the sound. They don't know the instruments that might have been played. They don't know if sound was made inside the tomb for the people outside the tomb or if that was made outside of the tomb for the priest inside the tomb. So, this… We now have the tools to realize hypotheses, to say, this is what it sounded like at this. This is what it sounded like at this. And we're able to sort of create these scenarios, which, to my delight, archaeologists and Egyptologists find very useful.

Danièle Cybulskie: Well, it is very useful. And as… as you were talking about, I was thinking about pieces being performed or instruments being used within a space and thinking once we have figured out what the sound waves are doing, we could also figure out what it would feel like to be in the space, like, in a physical way. We could recreate that as well, especially for… the deaf or hearing-impaired could also experience awe in the same way, once we figure out what the physics are.

Jonathan Berger: Absolutely.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yeah.

Danièle Cybulskie: I love this.

Jonathan Berger: You're one step ahead of me, Danièle.

Danièle Cybulskie: Well, my imagination is running wild with this. You were going to tell us there's a consequence of using this one piece by DuFay. What is the consequence, do you remember?

Jonathan Berger: Well, one of the mysteries about this piece is that a theory arose in the early twentieth century that – or mid-twentieth century – that the piece was written to realize the proportions, the architectural proportions of the church. That theory has been refuted and then reborn by musicologists. Musicologists are fighting about it now. It's clear that the arithmetic proportions of the piece have something to do with architecture. Right. You build out the structure. And it's also clear that those proportions do realize the proportions of the dome. So, if you take the proportion of the dome to the floor and from the floor out to the end, the way the piece is written realizes these measurements, which for me is incredibly inspiring. Right. So here someone writes a piece to consecrate this church and they're studying the architectural drawings, the architectural proportion of the church to realize this piece. Now the refutation is that it was really realizing the biblical proportions written about Solomon's Temple. Whether that's the case or not doesn't really concern me. I just find it inspiring that architecture drives music and music drives architecture.

Danièle Cybulskie: Yes. Well, it begs a type of question that medieval people would have been really interested in, which is if we can reconstruct Solomon's Temple, then we can reconstruct what it would sound like in Solomon's Temple. And this is something that medieval people would definitely be interested in. Yeah. What is it like to be in there? So, I need to ask you the question: you started this journey as a composer thinking about reverberation, about space. So how has this affected your own writing? Have you come back around? Are you starting to write medieval-themed pieces? What's going on with your own work?

Jonathan Berger: I don't write medieval-themed pieces, although I do in a way. Medievalism is constantly – I'm that old – so, medievalism is sort of constantly in the… particularly the operas and dramatic work I write. But I'm very much aware of acoustics and space when I write, more so now than ever. And in ideal situations – it doesn't happen very often, but – I sometimes get commissions where I know the space that I'm writing for and I'm able to go visit that space and even model it and then come back and say, I'm writing a piece that's specifically written – it's a site-specific space, site-specific for the acoustics of that space. And that, to me is… That's a great joy.

Danièle Cybulskie: Well, and I love that you're bringing this up because I think that this is something that maybe people wouldn't have thought about when they thought about medieval compositions, that composers are thinking of this space when they're creating these, because it is an important part of the creation of music as it's being made for the first time. I think with medieval music, sometimes it feels like it's timeless, but there are people who are writing this stuff down.

Jonathan Berger: Yeah, yeah. So, if people want to go onto my website, they can see our work on... There's a small church in Rome called Sant’Aniceto in Palazzo Altemps. Duke Altemps was a fascinating person. Again, we're a little bit beyond, we’re now in the 1600s. So, early 1600s, Duke Altemps builds a church in his palace in his palazzo. He's a polymath. He's interested in astronomy, he's interested in books. He writes plays, he collects musical instruments, and he writes music. And he was deeply involved in the architecture of this church. So, we have a little sweet spot here where we have someone who's thinking about music. And so, parenthetically, he's the person who brought Galileo to Rome to meet the pope and show off his telescope. So, this is a person who's in touch with intellectual thought. He builds this church and is involved in the architecture. He writes music. Although it's not clear that he wrote music for the church, we proved that, I think. But he also collected, he also commissioned all the music to be written in this church. And that's collected in a volume that we've edited and published. So, here we have this sweet spot. We have a church that hasn't changed since it was built. We know all the music that was written for it, much of which has not been performed since the 1600s. And we know that he wrote music, and we know that the music that he wrote, and he was involved with architecture. The music that he wrote, I think we've proven, was written specifically for this little church. When we perform it… when we perform it in other churches, it sounds like blank, blank, blank. But when we perform it in the church, it just sounds crystal clear and rich and beautiful. So those are the sweet spots. Those are sort of the golden moments that I'm looking for in my research.

Danièle Cybulskie: So as we wrap up, because we are coming to the end of our time – and right after we finish talking, I'm going to be playing those pieces, the dry piece clip, and then the whole piece that you recorded that is meant to tell us what it sounded like in the Duomo – so, before we leave, what is it that you want people to think about with all of this research that you've done? When people encounter medieval music or when people encounter medieval spaces, what do you want them to be thinking about?

Jonathan Berger: I think you actually articulated it much better than I could. Right. I want people to think about going into these spaces not as tourist sites and not as sites that they have to cross off their bucket list of, I've been to this church, I've been to that church, but as sites that were incredibly and deeply meaningful to everyday people at the time. And in order to do that, you have to think about it sensually. You have to think about what are the acoustic attributes of this space. There's a whole new field in research called sound studies, which tries to recreate the sound of towns and villages at a certain time. Right. And so, one walks through Florence, which is now, you know, completely full of honking horns and all this stuff. If we're able to eliminate all of that and understand what it was like to walk on a particular cobblestone street, what happened between the walls here and the echoes, these affected life dramatically. And so, I think the takeaway of this is we need to use our ears more sensitively and incorporate them into the experience of understanding a historical period, medieval or otherwise.

Danièle Cybulskie: I love it. And so, we're going to be leaving people with your website and they can listen to these samples and hopefully follow your research and learn what it sounded like for Incas or for people in ancient Egypt. Thank you so much, Jonathan, for being here.

Jonathan Berger: My pleasure. Great to talk to you, Danièle. Take care.

Danièle Cybulskie: Now that we've heard all about Jonathan and his team's work, it's time to give it a listen for ourselves. First, here is a two-second clip of what Guillaume DuFay's piece Nuper Rosarum Flores sounded like in a dry room. And now it's time for us to travel back in time and stand under Brunelleschi's famous dome in in Florence, 1436.

[Nuper Rosarum Flores performed by Stile Galante]

To find out more about Jonathan's work, you can visit his faculty page at Stanford University. You can find the Sound, Space, and Sensing the Unfathomable Project, as well as its images and audio samples, at ccrma.stanford.edu/trt

With this episode, we're now into February, the month of love, so it's time to dig up some medieval words on love and relationships.

Going into February, some of us may feel more inclined to agree with the cynical troubadour Bernart de Ventadorn, who says, “he who loves has lost his mind.” Sometimes it can definitely feel that way. But here's another quote that might be a little bit more encouraging to take us into the month. This is from the troubadour Cercamon, who says, “no matter how you serve this love, it will pay you back a thousandfold. To those who do it well, come honor and joy and all.”

For both of these quotations, as well as an entire chapter of medieval advice on how to woo your beloved, you can check out my book, Chivalry and Courtesy: Medieval Manners for a Modern World.

Thank you to all of you for supporting this podcast by letting the ads roll, sharing your favorite episodes and becoming patrons on Patreon.com. Thank you especially to everyone who participated in my first live Ask Me Anything video on Patreon, as well as those who watched it later. Talking about medieval stuff with you in real time is my favorite thing to do, so I appreciate your being there. If you're not yet a patron and you want to find out more, please check out patreon.com/themedievalpodcast

For the show notes on this episode, a transcript, and a huge collection of the books featured on The Medieval Podcast, please visit medievalpodcast.com. You can find me, Danièle Cybulskie, on social media @5minmedievalist or Five-Minute Medievalist.

Our music is by Christian Overton.

Thanks for listening and have yourself an amazing day.